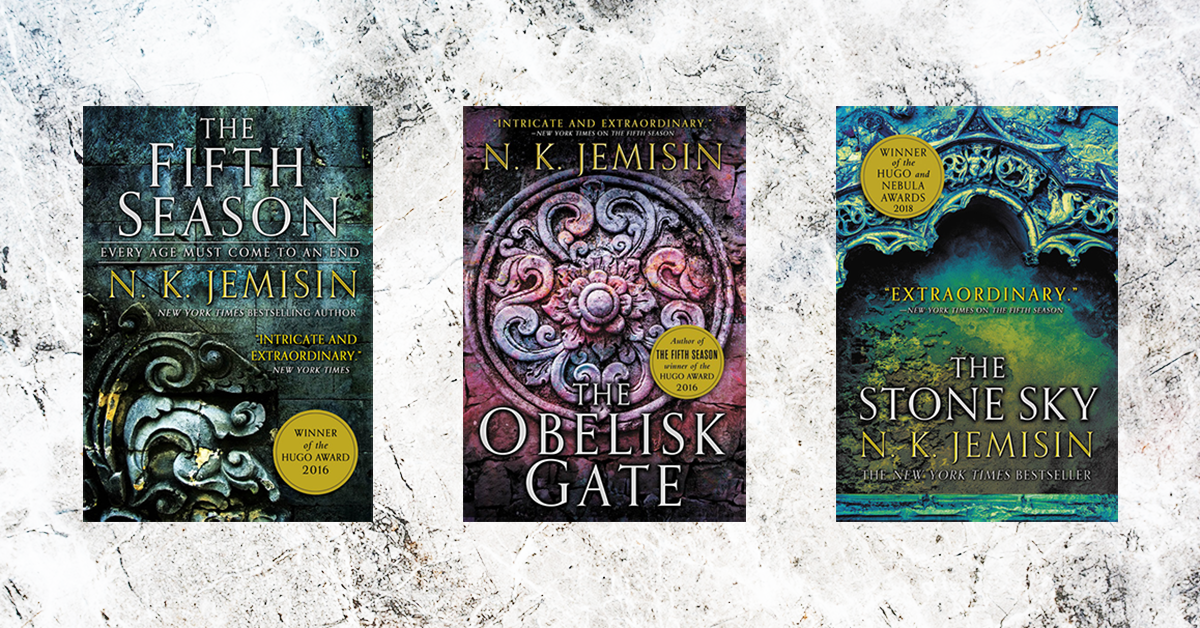

The Broken Earth trillogy by N.K. Jemisin

I own a debt of gratitude to the person who told me to read The Fifth Season by N. K. Jemisin. The Fifth Season is the first book in The Broken Earth trilogy, and all three books are remarkable.

I want you to read these books. But I am struggling to find a way to recommend them while telling you very little about them. I am glad I went in to this series cold.

In fact, I am glad for many reasons that I did not search for reviews in advance (fear not - this is a recommendation, not a review). I am not sure if Google is broken, or if the internet is populated with exceptionally bad takes, or both. After concluding the series, I searched for reviews to see if others feel the same way that I do. The top results were one star reviews on Google and Goodreads and Reddit, none more than a few sentences. Those reviewers were all angry about the publisher's font, or the author's race, or the characters' sex, or some vile combination thereof. The three star reviews were more baffling. While they were less overtly racist and misogynistic, they left me questioning if we read the same books. So many were riddled with forced, faulty analogies to other books only to say... what? I love this less than the thing I love the most? I do not understand those takes. My views did, however, mostly square with reviews in The New York Times and NPR (see below).

Anyway, back to my recommendation, in which I attempt to persuade you to read these books while telling you nothing substantive about them.

Start with a world as fully fleshed-out as anything written by your favorite science fiction or fantasy author. Then, add rules to that world that reveal themselves over the entire series. Into that world, place characters with distinct voices and logical motivations. Then, go beyond all the these-should-be-table-stakes mechanics to craft a story in which we actually give a damn about the people who populate these books. I agree with Naomi Novik's review for The New York Times:

Fantasy novels often provide a degree of escapism: a good thing, for any reader who has something worth escaping. Too often, though, that escape comes through a fictional world that erases rather than solves the more complex problems of our own, reducing difficulty to the level of personal struggle and heroism, turning all obstacles to monsters we can see and touch and kill with a sword. But N.K. Jemisin's intricate and extraordinary world-building starts with oppression: Her universes begin by asking who is oppressing whom, what they are gaining, what they fear. Systems of power stalk her protagonists, often embodied as gods and primeval forces, so vast that resistance seems impossible even to contemplate. When escape comes in her novels, it is not a merely personal victory, or the restoration of a sketchy and soft-lit status quo. Her heroes achieve escape velocity, smashing through oppressive systems and leaving them behind like shed skins.

In 2016, The Fifth Season won the Hugo award for best novel, making N.K. Jemisin the first Black author to win in this category (Octavia E. Butler won Hugo awards for Best Short Story and Best Novelette). The Hugo awards are not immune from criticism. Reasonable and well-intentioned people can debate whether one book is better than another in any given year. My own view is that such debates are a little bit silly and occasionally harmful. That said, there are worse indicia of quality than the Hugo.

A year later, Jemisin did it again with The Obelisk Gate. Back-to-back Hugo award are rare enough, let alone for books that are second in a series of three. In my experience, middle books are often the weakest – but not in this instance. I agree with Amal El-Mohtar's NPR review:

The Obelisk Gate is the second book in a trilogy that makes me forget everything people say about second books in trilogies. ... If anything it's even more engrossing than The Fifth Season, picking up right where that first book left off and plunging us deep into the Evil Earth and all its machinations. Not only could I not put it down — I couldn't come up for air long enough to comment on it while forsaking sleep and food in order to finish it.

Again – and I can't stress this enough – all of Jemisin's beautiful world-building is in service to character development and, ultimately, to the story itself. Books like these sometimes fall into a trap by focusing exclusively on how the characters do what they do at the expense of crafting a story about why the characters do what they do. I will make an analogy that I hope works better than the bad takes noted above: In The Hunt for Red October, Tom Clancy gives us a lot of information about how nuclear submarines work in order to tell a compelling story with compelling characters that (mostly) takes place in nuclear submarines. Clancy's presentation of the "world" of submarines is a fascinating and necessary component of the book. But a detailed explanation of sonar systems is not a story in and of itself. Rather, that information drives plot, establishes motivation, and imbues some scenes with heart-pounding suspense. Functionally, N.K. Jemisin does the same thing. Her world building forms an engine that sets characters in motion and establishes the stakes in play.

And boy are those stakes high, even relative to the staples of the genre. This story is not about whether a hero can save the world, but whether the world is worth saving.

Jemisin's characters are fully realized people, navigating systems oppression and control during a time of calamity. Their goals conflict and their methods are incompatible. And, because the characters are fully realized people, their goals and methods evolve over time and in response to the world around them. Forgive another analogy, but reading The Broken Earth feels like playing your best D&D sessions. Mechanics feed story feed mechanics feed story and on and on and on.

A year after the Obelisk Gate, Jemisin scored a hat trick with yet another Hugo for The Stone Sky. I'm not an author, so I can only imagine how difficult it must have been to bring this story to its conclusion. I agree with Andrew O'Hehir's review for The New York Times, which is both a review of the book and the series as a whole. I agree even more (and again) with Amal El-Mohtar's NPR review of the Stone Sky. Those reviews do not include spoilers per se, but it is hard to quote from them without revealing more than I'd like to. Instead, I will say that N.K. Jemisin uses The Stone Sky to prove her thesis – or what I perceive to be her thesis. The Stone Sky's primary narrator says:

Some worlds are built on a fault line of pain, held up by nightmares. Don't lament when those worlds fall. Rage that they were built doomed in the first place.

Of that sentence and others, El-Mohtar writes:

I ate these sentences up and only felt hungrier for more: the affirmation of anger, the recognition of hidden horrors, the rejection of docile complicity. ... For how many people on our planet has the world ended, sometimes multiply in one lifetime, in order for others to preserve a certain lifestyle? For how many millions is weathering apocalypse the norm, a matter of course?

I agree. My temptation is to say something like, "this has never been more important." But that is true in every season.

Tags: Books, RecommendationsSubscribe: RSS/Atom feed for your reader of choice.